A Short History of the University of Iowa Institute for Vision Research

Edwin M. Stone, M.D., Ph.D.

July, 2020

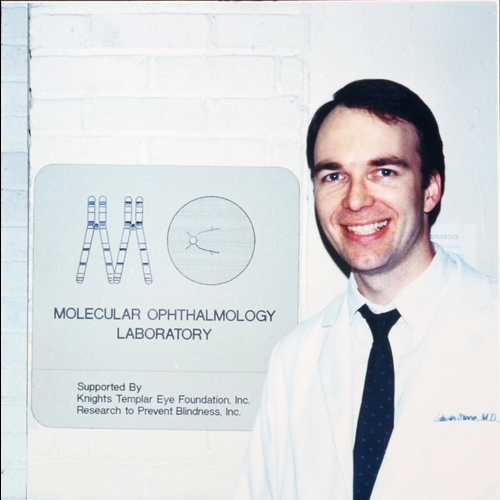

MOL Years (1986-1997)

In July of 1986, Ed Stone and his wife Mary, a dermatologist, came to Iowa City for Ed's ophthalmology residency and Mary's first faculty position. Ed was attracted to Iowa for many reasons, one of which was Stan Thompson and Jim Corbett saying, "you should come here!" when his resident applicant tour group poked their heads into neuro-ophth morning rounds during their tour. Another was Iowa's famous faculty that at the time included (in addition to Thompson and Corbett), Fred Blodi, Bob Watzke, Sohan Hayreh, Bill Scott, Joerg Kolder, Tom Weingeist, Jim Folk, Rick Anderson, David Tse, Frank Judisch, Jay Krachmer, Chuck Phelps and Karl Ossoinig. But, perhaps most important was the interest that the residency selection committee expressed in Ed's desire to use his graduate training in molecular biology to study inherited diseases of the eye. Tom Weingeist was a member of that selection committee and encouraged Ed to set up a molecular biology lab shortly after his arrival. In fact, Tom decommissioned the electron microscope that he had used years earlier for his PhD work in the department and gave Ed access to that space (Med Labs room 361) in the beginning of 1987. The sign that Ed proudly placed outside that room at the time is to his knowledge the first use of the term "Molecular Ophthalmology."

-

Ed Stone stands outside the original Molecular Ophthalmology Laboratory, 361 Med Labs (1987). -

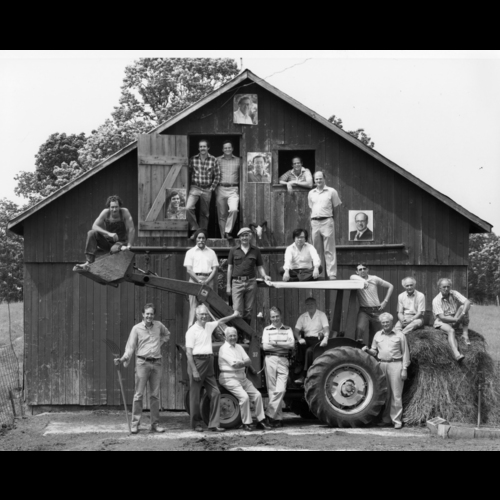

Faculty of the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology in 1983. Top row: Bill Scott. Row 2, left to right: Rick Anderson, Frank Judisch, Andy Packer, Jim Corbett, Tom Weingeist, Jim Folk, Jay Krachmer, Karl Ossoinig. Row 3, left to right: Sohan Hayreh, Stan Thompson, David Tse. Bottom row, left to right: Chuck Phelps, PJ Leinfelder, Al Braley, Bob Watzke, Fred Blodi, Paul Montague, Mel Chiles, Joerg Kolder, Terry Perkins. -

A hospital car transports ophthalmology patients to and from the clinic (1941). Courtesy University of Iowa Special Collections. -

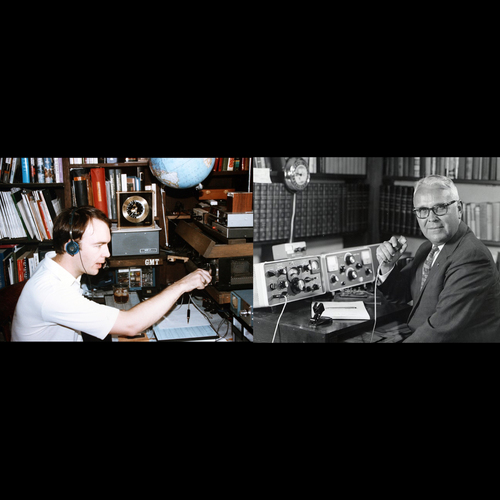

Ed Stone (NV5K, left) and Al Braley (W0GET, right) are the only known members of the Iowa ophthalmology faculty to have held active amateur radio licenses while on the faculty. Braley's state-of-the-art equipment was manufactured by Collins Radio in Cedar Rapids.

Outreach has been one of the fundamental cultural features of University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics since their inception. An efficient "hospital car" system operated for decades to bring patients from around the state to Iowa City for care and Dr. Alson Braley even ran an amateur-radio-based network for identification of human tissue for corneal transplantation when he was chairman of the ophthalmology department in the 1960s. In fact, one morning shortly after his arrival in Iowa, Stone was driving to work and talking with an older gentleman using the portable ham radio he had in his car. The man asked what brought Ed to Iowa and he proudly told him that he was an ophthalmology resident. After a startled pause, the man said "You know that conference room you're about to go into for rounds? It's named after me." Ed eventually had the pleasure of meeting Al Braley in person, and to this date, the two of them are the only Iowa ophthalmology faculty members to have had active amateur radio licenses.

In the late 1980s, the human genome was being mapped at low resolution by identifying "linkages" between genetic markers whose locations were known and new markers whose genomic locations were previously unknown. The same methodologies used for this mapping work could also be used for identifying the chromosomal locations of disease-causing genes if one had access to families with enough affected individuals (ideally 15 or more) who were willing to participate. While taking a history and examining a child who was going to have surgery for an unrelated condition, Stone discovered that the child's mother had a macular dystrophy and many additional affected relatives. The first of many Molecular Ophthalmology Laboratory "road trips" consisted of Stone examining dozens of members of that family in a Des Moines restaurant that the family owned. The informed consent document was less than one page long in those days and the "clinical equipment" consisted of an eye chart, indirect ophthalmoscope, dilating drops and phlebotomy supplies - all transported to the restaurant in paper grocery sacks. The samples gathered that night led to the lab's first major discovery, the chromosomal location of the gene causing Best disease.

-

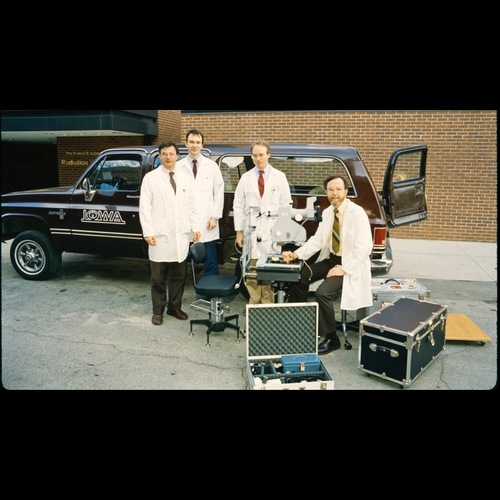

Loading the truck for an early MOL road trip (1987). Left to right: Tom Weingeist, Ed Stone, Mark McCarthy and Ed Heffron. The 30 degree Zeiss fundus camera in the photograph was borrowed from the clinic for the weekend and returned to service Sunday night. -

Packing complete (1987). -

Some road trips were made using Stone's 1978 Buick Estate Wagon for transportation. It required frequent administration of transmission fluid purchased at convenience stores to keep it going. Clockwise from upper left: Ed Stone, Natalie Neill, Jill Brody and Kristin Wells (1987). -

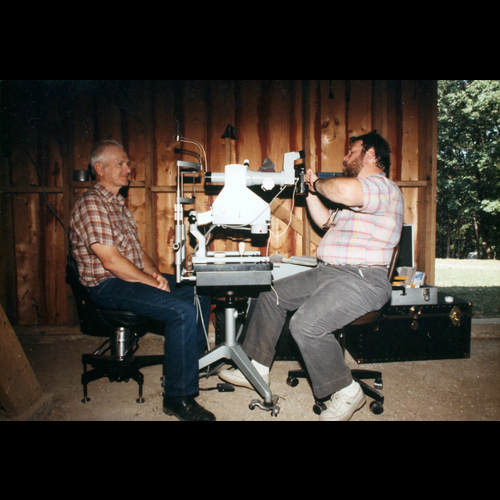

Bill Ward (right) photographs a research subject in his family's dirt floored pole barn (1988). -

Stone examines a young research subject during a road trip as the youngster's father and brother look on (1987). -

Another early road trip. The group has added a slit lamp bolted to a hospital bed table and an EOG instrument (between Nichols and Stone) built in Stone's garage. Left to right: Tim Johnson, Gina Perri, a student volunteer, Brian Nichols, Ed Stone, Natalie Neill, Aaron Weingeist and Ed Heffron (1988).

Also in 1987, Stone received his first grant from the Knights Templar Eye Foundation, for $19,600. This grant was the sole support for the lab for its first year of operation. All the lab members were volunteers including other Iowa ophthalmology residents (Kristin Wells, Tim Johnson, Mark McCarthy and Steve Bennett), junior faculty (Alan Kimura), ophthalmic photographers (Ed Heffron and Bill Ward), medical students (Mike Raphtis, Chuck Barnes, Jill Brody, Jeff Coppinger and Brian Weismann ) and undergraduate students (Natalie Neill, Laura Vockrodt, Reid Longmuir and Aaron Weingeist). The team moved up from grocery sacks to footlockers for carrying their equipment. They added a slit lamp, a Zeiss fundus camera, and a home-made EOG instrument. They transported all this gear in vans borrowed from the University motor pool (usually used to transport small athletic teams to regional games). In 1987 alone, this volunteer team examined families that eventually led to the chromosomal location and/or identification of the first human glaucoma gene (MYOC) as well as the genes causing Best disease (BEST1), pattern dystrophy (RDS), Stargardt-like Dominant Macular Dystrophy (ELOVL4), Autosomal Dominant Neovascular Vitreoretinopathy (CAPN5), Lattice, Granular and Avellino Corneal Dystrophies (TGFB1), Posterior Polymorphous Macular Dystrophy (OVOL2), and Wagner Disease (VCAN1).

Stone completed his 3.5 years of residency in December of 1989 and joined the faculty as an assistant professor the following month. During his first 2.5 years on the faculty, he split his time between directing the fledgling Molecular Ophthalmology Laboratory (MOL) and completing his fellowship in vitreoretinal diseases and surgery. In 1990, Val Sheffield joined the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Iowa and brought with him the means for unlocking the power of the blood samples that Stone had collected and catalogued during his residency. During his fellowship in San Francisco, Val had perfected a method for polymerase-chain-reaction-based mutation detection of disease-causing mutations in human blood samples. Ed and Val first met when Val was interviewing for his faculty job, and within days of Val's arrival he dropped into the MOL to tell Ed that he had decided to take the job and was opening his lab in the adjacent building (EMRB). During that meeting Val told Ed that he had a powerful new method for detecting mutations and Ed responded that he had a freezer full of DNA samples from patients with inherited retinal diseases to test the method with. Ed handed Val a box of samples and less than 24 hours later, they had their first mutual discovery: an Arg58Thr rhodopsin mutation in a family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. The paper reporting this discovery was the first of more than 160 research papers (so far!) that Ed and Val have published together.

-

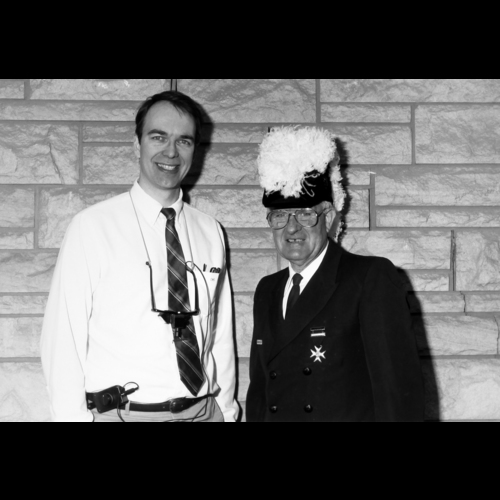

Howard Walden, representing the Knights Templar Eye Foundation (left), congratulates Ed Stone (right) on the receipt of his first grant (1987). -

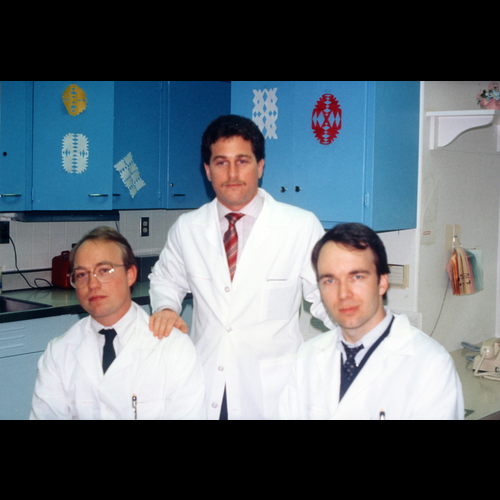

In the 1980s, Iowa started three new ophthalmology residents every six months and the residency lasted 3.5 years. Pictured here are the July-December 1986 group, left to right: Mark McCarthy, Lee Birchansky and Ed Stone. The location is the 2 tower nursing station from which all the histories and physicals for the following day's surgeries for the entire department were performed by the new residents at the end of their regular work day. -

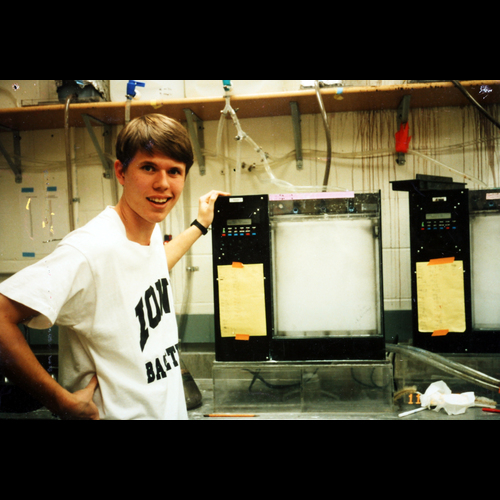

Reid Longmuir stands in front of an automated silver staining device (gonculator) used to detect DNA in polyacrylamide gels (1990). The prototype of this device was built in Stone's basement and used cascaded resistor-capacitor timing circuits to trigger relay-controlled dishwasher valves. -

Ed Stone (left) and Ed Heffron (right) prepare to photograph a patient with the workhorse 30 degree Zeiss fundus camera (1990). -

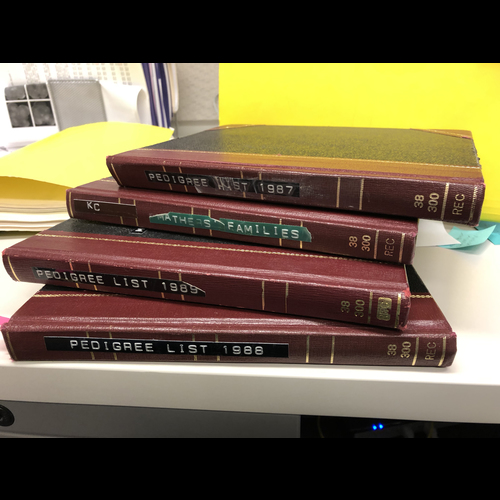

Handwritten family log books from MOL during Stone's residency. Many of the lab's most important findings, including the discovery of the first glaucoma gene, were made using the families gathered during this period and recorded in these books.

The year 1990 was also very notable for the addition of Luan Streb as the MOL's first full time employee. Luan was a research assistant in the photograph reading center of the department when Ed asked her if she would be willing to learn some molecular biology. Luan proved to have an extraordinary talent for managing complex tasks of all sorts and in the early years did everything from preparing reagents and running gels to purchasing supplies, managing the lab workforce and typing grants and papers. In 1992, she helped Stone draft a written "expectations of MOL employees" document that set a standard of performance that as much as any other single management concept helped the lab and later the center and institute to be successful. A mother of four and now grandmother of seven at the time of this writing, Luan is still pursuing cures for blindness as the chief operating officer of the Institute for Vision Research.

The first seven years of the 1990's were marked by explosive growth and productivity. Kim Vandenburgh, Chris Taylor, Louisa Affatigato and Carmella Wiles joined the staff as research assistants; Linda Koser joined as secretary; Brian Nichols and John Fingert were Ed's first two MD/PhD graduate students; Elise Héon and Arlene Drack were his first two molecular Ophthalmology fellows; David Brown, Jerry Brown and Rob Mack collaborated on projects during their residencies and fellowships in the department; and Lee Alward, Bob Folberg, Jay Krachmer, Bill Mathers, Mike Wagoner and Jim Folk contributed their faculty expertise. During this period the group also formed a number of valuable and very long-lived collaborations outside Iowa, with Jerry Fishman, Dick Weleber, Sam Jacobson, Art Cideciyan, Don Gass, John Heckenlively, Al Maguire, Jean Bennett, Byron Lam, Michael Gorin and Francis Munier. From 1990-1997, this talented group of people published 75 papers together culminating in the paper describing the first human glaucoma gene (which has since been cited more than 1400 times).

-

Luan Streb in the "administrative suite" of the MOL (2000). -

Left to right: Val Sheffield, Brian Nichols, Ed Stone, Hunter Rawlings (President of the University of Iowa), Elise Hon (1994). -

Left to right: Ed Stone, Dick Weleber, Paul Sieving, Jerry Fishman, Sam Jacobson. -

Left to right: Tom Weingeist, P. Namperumalsamy, Ed Stone, Culver Boldt, Dick Weleber, Jim Folk, Alan Bird, Andrew Lotery (1997).

CMD Years (1997-2010)

In 1997, Stone recognized that two things were driving the MOL's success: true collaboration among scientists with different but synergistic expertise; and, an unwavering focus on patients. Although his and Val's initial collaboration had been somewhat providential, he felt that similar collaborations could be intentionally fostered by a trans-departmental organization devoted to translational vision research. He also recognized that NIH grants were individually too small and too narrow in scope to power long-term interdisciplinary collaborations and that major philanthropy would be needed. For optimal philanthropic messaging, he chose to name the new organization after the most common disorder under investigation by the group: age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Weingeist and Stone traveled to St. Louis and succeeded in recruiting a very established group of AMD scientists to Iowa City: Greg Hageman, Steve Russell, Karen Gehrs, Markus Kuehn and Rob Mullins. At the same time, Val recruited an established gene discovery scientist, Bento Soares, to the department of Pediatrics. Tom Casavant in Iowa's department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Bev Davidson a gene therapy scientist in the Internal Medicine Department also joined the group. In September of 1997, the vision research efforts of Stone, Sheffield, Casavant, Soares, Hageman and Davidson were combined to form the University of Iowa Center for Macular Degeneration.

-

MOL laboratory photo 1997. Top row, left to right: Justin Rosenow, Kelly Eslinger, Brie Romines, Kelly Kopp, Rich Allen and Brian Lopp. Middle row: Heidi Haines, Paula Moore, Louisa Affatigato, Chris Taylor, Ed Heffron, Ed Stone. Front row: Andrew Lotery, Luan Streb, Jean Andorf, Kim Vandenburgh. -

Jack Johns, the founding member and also first chairman of the Center for Macular Degeneration Advisory Board (2000). -

An early Advisory Board dinner at the 126 restaurant in downtown Iowa City (2000). Left to right: Steve Russell, Leo Hauser, Rob Mullins. -

An early Advisory Board dinner at the 126 restaurant in downtown Iowa City (2000). Left to right: Ed Stone, Mark Wilkinson, Jack Johns. -

Godzilla, the unofficial mascot of the CFCMD and later IVR in his hand-knitted Hawkeye scarf and mittens, flanked by Luan Streb (left) and Dianna Brack (right).

A scientific meeting was held to celebrate the creation of the new Center and academic ophthalmology luminaries from around the world attended. Alan Bird was the keynote speaker. The early CMD years were marked by a "British invasion" of two outstanding research fellows from the UK: Andrew Webster and Andrew Lotery. At the time of this writing Andrew Webster is the head of the Inherited Retinal Diseases unit of Moorfields Eye Hospital in London and Andrew Lotery is the Chairman of Ophthalmology in Southampton. In the late 90's, Webster tackled the problem of the extreme allelic heterogeneity of ABCA4 and helped demonstrate that this gene does not play a meaningful role in age-related macular degeneration (quite controversial at the time!). Lotery coupled positional cloning and candidate gene screening to identify the gene responsible for Doyne Honeycomb Macular Dystrophy, Malattia Leventinese, and Autosomal Dominant Radial Drusen; diseases that were thought by some at the time to be distinct entities. The Malattia project was greatly aided by Ed's former fellow Elise Héon who spent a year in Switzerland with Francis Munier ascertaining the families affected with this disease living in the Leventine Valley. Héon later became the chairman of ophthalmology at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

The year 1997 was also very noteworthy for the addition of a talented young scientist Jean Andorf. Jean joined the lab as a research assistant right out of college and intended to become a physician's assistant to maximize her chance of finding a job near her husband who was an emergency medical technician in Bettendorf, Iowa. However, Stone quickly recognized that Jean's uncanny ability to think in multiple dimensions of time and space and her photographic memory for genetic and clinical details would make her an unusually valuable asset to the lab's genetic testing and gene discovery efforts. Stone persuaded Jean to pursue her career at the University of Iowa and 23 years later - despite living in Bettendorf and commuting more than 100 miles per day - she is still making major contributions to the IVR mission in her dual role as lab manager of the Molecular Ophthalmology Laboratory and technical director of the Carver Nonprofit Genetic Testing Laboratory.

-

Jean Andorf (1997). -

Left to right: Luan Streb, Paula Moore, Louisa Affatigato, Jean Andorf, Cami Opfer, Chandrika Vira (2000). -

Silver staining room (2000). At the peak of SSCP mutation detection and STRP genotyping, the lab electrophoresed and interpreted forty 60-lane gels per day (2400 PCR reactions). -

Val Sheffield (left) and Ed Stone (right) shortly after moving their labs to the MERF building (2002). -

Celebrating John Fingert's successful thesis defense. Left to right: Brian Nichols, Ed Stone, John Fingert (2000).

Stone realized that it was unlikely for the conventional philanthropic mechanisms of the University to view a single research group in a relatively small department to be sufficiently important to generate the major philanthropy that would be needed to take the group to a "top ten" level of research capability. So, he asked four individuals if they would be willing to help him form an advisory board to raise money and help the group advance its "curing blindness" agenda within the University. The first of these was Jack Johns, a successful businessman from Cedar Falls, IA whose daughter had recently been diagnosed with a Stargardt-like condition. Jack used his charismatic persuasiveness to recruit a Washington (D.C.) attorney friend of his, Paul Rosenthal, to the cause. Leo Hauser was a patient of Stone's with retinitis pigmentosa who made the mistake at the end of one of his clinic visits to ask if there was any way that he could help the effort. Stone said "YES!" and recruited him to the board on the spot. Leo Hauser was at the time the president of a toy manufacturing company in St. Louis who reintroduced Godzilla and associated characters to a new generation of imaginative children. Gary Seamans, the fourth original board member was the son of one of Ed's AMD patients and was similarly recruited in the context of his mother's care. Gary grew up in Iowa City and received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Iowa. He and his wife Cammy are the namesakes of the University's engineering building. These four extremely successful people came together for the first time in 2000 to brainstorm with Stone how they could best help the cause. At one point in the meeting, a near term goal of $40,000 was suggested. By the end of the day, the goal had grown to $7M. Rosenthal confided to Ed some years later that had the goal remained $40,000 he would have just written a check and never come back!

-

An early Advisory Board meeting in Chicago. Although frugality is central to the IVR culture, the police tape in front of the hotel was judged to be a step too far. Left to right: Ed Stone, Mary Carver, Paul Rosenthal, Gary Seamans, Cammy Seamans, Ruth Carver, Leo Hauser, Luan Streb, Bruce Spivey (2001). -

Celebration of the Seamans-Hauser Chair of Molecular Ophthalmology. Left to right: Gary Seamans, Cammy Seamans, Ed Stone, Leo Hauser (2007). -

Left to right: Marty Carver, Roy Carver, Jr., John Carver (2007). -

The Medical Education and Research Facility (MERF) of the University of Iowa. The Institute for Vision Research occupies the top two floors of this building. -

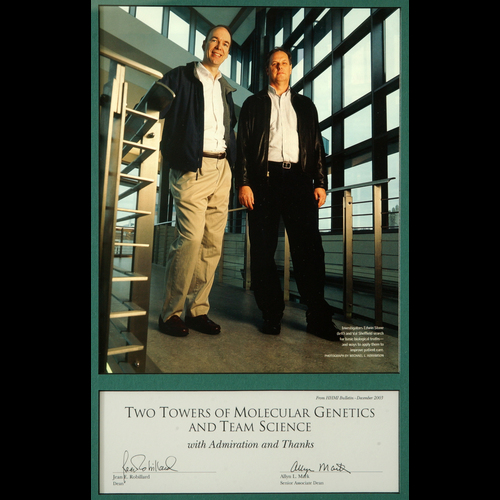

When a story about the collaboration between Ed Stone and Val Sheffield appeared in the monthly bulletin of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Deans Jean Robillard and Allyn Mark presented this "Two Towers" award to them "with admiration and thanks" (2003). -

Steve Kuusisto's guide dog Nira gets a drink from an HHMI mug (2010).

The new board met quarterly and gradually grew to include Cammy Seamans (whose mother was also affected with AMD), Ruth Carver (whose mother and siblings were affected with Best disease), Marty Carver whose parents are the namesakes of the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa and J. Nelson, a Chicago telecommunications executive who grew up in Boone, Iowa. In September 2005, the board led a strategic planning effort involving dozens of individuals from all across the University of Iowa campus to help clearly define the "brand" and mission of the CMD. The group decided that the Center for Macular Degeneration should aspire to become "THE" preeminent clinical and research organization in the field of retinal degenerative disease. One of the most enduring outcomes of this strategic effort was the creation of a one page "culture document" which has since served as the group's unofficial constitution.

In 2006, Gary and Cammy Seamans joined forces with Leo Hauser to create the first endowed chair in the center: the Seamans-Hauser Chair of Molecular Ophthalmology for Ed Stone. In 2007, Marty Carver and his two brothers Roy Jr. and John made a $10 million dollar gift to the University to name the center the "Carver Family Center for Macular Degeneration" and to create two additional endowed chairs, for Val Sheffield and Tom Casavant, as well as an endowment to create the John and Marcia Carver Nonprofit Genetic Testing Laboratory. At the time of this writing, the CNGTL has provided low-cost genetic testing to thousands of patients distributed across all 50 states and more than 60 other countries. Other advisory board members who joined the group during this period included: John Pappajohn, an entrepreneur and philanthropist from Des Moines; Bruce Spivey, a former faculty member of the department of ophthalmology at Iowa who spent most of his career at UCSF, Tim Sear, a former CEO of Alcon Pharmaceuticals; and John O'Brien a businessman from Cleveland, Ohio with a longstanding interest in vision research and support services for visually impaired people.

The creation of the Center for Macular Degeneration and its impressive advisory board captured the imagination of University leaders to the degree that the faculty of the center relocated to fourth floor of the newly constructed Medical Education and Research Facility on Newton Road in 2002. This move coincided with Stone's election to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute - the only practicing ophthalmologist ever elected to that organization. Val Sheffield had been elected to the HHMI five years earlier - further testament to the power of the synergistic culture that had grown from their initial collaboration a decade earlier. Other major recognitions for the group during the CFCMD years included The Cogan Award, The Doyne Lecture, and the Jackson Memorial Lecture for Stone and the American Association of Physicians and National Academy of Medicine for Sheffield.

-

"Play for LCA" was a philanthropic component of "Project 3000" sponsored by Derrek Lee of the Chicago Cubs. A Cubs game at Wrigley Field was dedicated to the cause of raising awareness of inherited blindness. Left to right: Rob Mullins, Lee Alward, Keith Carter; John Fingert, J Nelson, Luan Streb, Ed Stone, Heather Scherber, Todd Scheetz, Mitch Beckman, Terry Braun, Mark Wilkinson (2007). -

Ed Stone and Mina Chung stand beside a painting by Lee Allen, a faculty member of our department for many years and a student of Grant Wood (2002). -

Left to right: Ed Stone, UI President Sally Mason, and Herky the Hawk at an alumni meeting in Washington, D.C. (2011). -

Leo Hauser models a T-shirt made to commemorate the opening of the University of Iowa Institute for Vision Research (2010). -

The fourth floor of the MERF building looking north from the atrium in the early morning (2010).

In the year 2000, the entire inherited retinal disease community became focused on Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) when Jean Bennet and Al Maguire at the University of Pennsylvania showed that gene therapy could restore useful vision to dogs affected with this disease. The CFCMD team recognized that many patients would be needed for the inevitable human trials that would evolve from this work and set out to use their incomparable genotyping horsepower and referring physician network to identify and molecularly test every individual in the United States affected with LCA (estimated to be 3000 people). This effort was dubbed "Project 3000" and received major support from two major sports figures who had children affected with childhood-onset vision loss: Wyc Grousbeck, the owner of the Boston Celtics and Derrek Lee, then first baseman for the Chicago Cubs. The program succeeded in identifying more than 90% of individuals affected with LCA in the US under 20 years of age, the most treatable age group. During this same period, Mina Chung, a retina specialist at the University of Rochester and former fellow at the University of Iowa spent one week per month working on her K08 award in the CFCMD while continuing her clinical practice in New York.

In 2008, the advisory board repeated its campus-wide strategic planning effort with the enthusiastic participation of a new University president, Sally Mason. The findings of this effort were instrumental in the creation of the Institute for Vision Research two years later.

From 1998 through 2009, CFCMD published 207 papers together - 12 of which have already been cited more than 200 times. These included the discovery of genes involved in AMD, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Leber congenital amaurosis and the enhanced S-cone syndrome as well as a paper describing an efficient strategy for genetic testing of genetically heterogeneous disorders like LCA.

IVR Years (2010-present)

In the spring of 2010, Stone felt that the CFCMD's growth and development was being limited by the confines of the clinical department of ophthalmology, which like other academic departments across the country was under increasing pressure to deliver fee-for-service medical care. Given the important roles that other departments and other colleges had played in the CFCMD's success to date, Stone felt that it was time to codify this interdisciplinary culture into a trans-collegiate, trans-departmental institute with a director who would report to the Vice President for Medical Affairs instead of to a department chair or a dean. In July of 2010, this new structure was approved by Jean Robillard (VPMA), Paul Rothman (Dean of the Carver College of Medicine) and Keith Carter (Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology). The University of Iowa Institute for Vision Research was born!

In addition to the new administrative structure, the new institute was given an additional floor of lab space in the MERF building, increasing its footprint on campus to a total of 32,000 square feet. This additional space allowed John Fingert, Mike Anderson and Markus Kuehn to have contiguous laboratories and to solidify the Glaucoma Research Center as one of the major units within the new institute. Likewise, Todd Scheetz, Terry Braun, Adam DeLuca and their colleagues were able to create a contiguous bioinformatic research group to collaborate with all of the biologists in the adjacent labs. Rob Mullins was able to expand his Ocular Cell Biology Laboratory adjacent to Val and Ed, and was also able to expand and formalize the research eye bank that at the time of this writing consists of over 2700 eyes, most of which were collected and processed for histology, immunohistochemistry, RNA and DNA analysis within 6 hours of death. Seongjin Seo and Arlene Drack were also able to expand their labs while remaining very close to their collaborators.

-

Jan Riley makes a young patient feel at home. -

A typical view from Ed Stone's desk in the IVR: Budd Tucker holding thousands of dollars of tissue culture reagents in his hands, Louisa Affatigato racing to her next task, and Godzilla standing guard (2018). -

Celebration of Budd Tucker's investiture as the Howard F. Ruby Chair of Human Retinal Engineering in UI President Bruce Harreld's home in Iowa City. Left to right: Gary Seamans, Paul Rosenthal, Culver Boldt, Marty Carver (2019). -

Celebration of Budd Tucker's investiture as the Howard F. Ruby Chair of Human Retinal Engineering in UI President Bruce Harreld's home in Iowa City. Foreground, left to right: Budd Tucker, Rob Mullins, Brian Walker. Background, left to right: Mimi Carver, Gary Seamans, Marty Carver, Culver Boldt (2019).

A very important part of the evolution from center to institute was the addition of nurse Janet Riley to the team. Jan went to nursing school at Iowa before moving with her husband, a dentist, to Colorado for the first part of their careers. When they returned to Iowa City, Jan brought her years of nursing and clinic management experience to the inherited eye disease effort. In 2009, she joined forces with Mark Wilkinson, the vision rehabilitation specialist who had worked closely with Stone since his residency to expand Ed's inherited eye disease clinic to a multi-provider inherited eye disease service that at the time of this writing is the largest in the country. Jan single-handedly obtained the more than 3000 skin biopsies that gave rise to the IVR's incomparable collection of patient-derived cell lines and an even larger number of blood samples that fueled the institute's gene discovery efforts. However, Jan's and Mark's greatest contribution has been the creation and daily maintenance of a caring integrated environment that puts the needs of the patient first in every decision.

Despite all this growth and reorganization, Stone knew that there was a major hole that needed to be filled if the group was going to really change the way degenerative retinal diseases are treated - they still needed an accomplished stem cell scientist. Ed went to the 2010 ARVO meeting in Ft. Lauderdale with one and only one goal: to find a stem cell scientist he could recruit to the new institute. He visited every poster and listened to every talk that had stem cells in the abstract and one speaker stood out clearly among the rest: a 30 year-old instructor from Harvard Medical School, Budd Tucker. Ed went up to Budd after the talk and set up a meeting for the next day. At that meeting, Ed handed Budd a blank yellow pad and a pen and said: "write down everything you need to cure blindness and I'll get it for you." A few days later Budd called to express some concern that there weren't any other stem cell scientists in the IVR. Ed asked, "is that a good thing or a bad thing?" Sixteen weeks later, Budd and his wife Gillian closed on their new home in Iowa, one day before his job was officially approved by the college of medicine. Ed told Luan later that day, "You know, I need to cut back on the salesmanship just a little bit so that they'll close on their house the day AFTER they get their job."

What Ed didn't fully realize during this recruitment was that Budd had grown up on the deck of a 150 ton commercial fishing vessel with a crew of 14 grizzled men aged 18 to 60 who fished the icy Atlantic ocean 200 miles northeast of Newfoundland for 8 days at a time. It turned out that commercial fishing (with all of the associated welding, drilling, lifting, pitching, problem solving, planning, navigating, leading and in-your-face "conflict resolution") was the perfect preparation for a major role he would play in the IVR: the conception, design, construction, certification, funding, and leadership of what is now known as the Dezii Translational Vision Research Facility and the Ruby Human Retinal Engineering Laboratory.

-

One of the commercial fishing vessels owned and operated by Budd Tucker's family. Budd skippered this boat during his college years (1998). -

Chalk talk in Mullins' office. Left to right: Rob Mullins, John Fingert, Steve Russell, Budd Tucker (2016). -

Computational biology twins separated at birth: Todd Scheetz (left) and Terry Braun (right) (2017). -

Summer transportation in the IVR. Left to right: John Fingert (Porsche), Ed Stone (Ford), Rob Mullins (Jeep), 2017.

Perhaps the most important thing in science is to "ask the right question;" that is, to understand a problem clearly enough to envision the key to its solution, even when the solution itself might take years of additional effort. The most important "right question" moment in the entire history of the IVR occurred shortly after Tucker arrived and started configuring his lab to function in a "good manufacturing practices" (GMP) fashion so that IVR physicians could ultimately transplant stem-cell-derived retinal cells into their patients. At this point in time, most groups assumed that gene replacement therapies would be devised with a corporate partner because "everybody knew" that it cost at least a million dollars to manufacture one batch of an adeno-associated-viral therapeutic to FDA standards. However, as Stone watched the proposed price tags for such therapies inch toward a million dollars per patient or more, he realized that very few patients would actually be treated until the treatments could be delivered for much less money.

One day during a lab meeting Ed asked Budd the key question: "if you owned your own GMP manufacturing facility, how much would it cost to make a batch of AAV virus?"

Budd replied, "About $20,000."

Ed protested, "No, I mean personnel, reagents, equipment, everything."

Budd said, "Really, we could do it for about $20,000 per batch."

Ed asked, "Well how much would it cost to build a GMP facility?"

Budd replied, "About three million dollars."

So, that was the answer to the whole problem! Gene therapies only cost a million dollars per batch if you had to use a for profit GMP facility to manufacture them. If you could build your own GMP facility in a non-profit public university, you could re-use it for batch after batch and gene after gene at a cost of only $20,000 to make enough virus to treat 50 patients ($400 per patient). Then, if your academic retinal surgeons could do the surgery at "cost" (about $3000 per surgery), and your molecular diagnostic unit could find a person's disease-causing mutation for less than $1000, and if follow up study visits could be done for $1000 per year or less, you could deliver a gene therapy with ten years of follow up for less than $20,000 per patient - 40-50 times less than commercial treatments.

The senior faculty of the IVR at that time included Ed Stone, Val Sheffield, Budd Tucker, Rob Mullins, John Fingert, Todd Scheetz, Terry Braun, Mike Anderson, Markus Kuehn, Arlene Drack, Seongjin Seo, Steve Russell, Culver Boldt and Elliott Sohn. This group met for two hours every two weeks to discuss their overlapping scientific interests and from these discussions the mature vision of the mission of the new institute emerged: we would "leave no one behind." That is, we would treat all molecular forms of inherited retinal disease and glaucoma regardless of how rare they were or how advanced a patient's disease was when they presented to us. We would use gene therapy to slow down or stop early forms of the disease, and stem cell transplantation to restore vision to people who had lost it. And, we would do it all in a nonprofit manner with non-proprietary instruments and reagents to keep the cost of the treatments as low as possible.

-

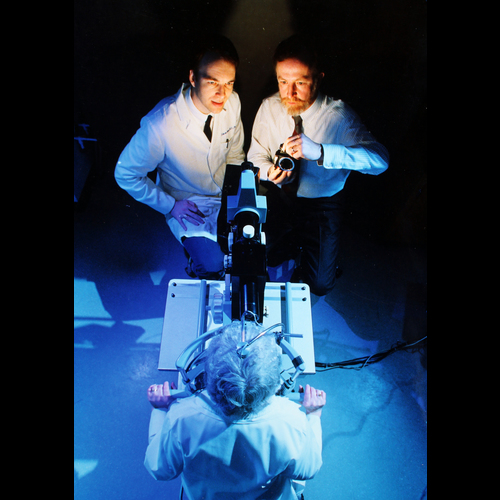

Steve Russell reaches for the syringe containing the first AAV-mediated gene replacement therapy (RPE65) administered to the retina at the University of Iowa (March 26, 2013). -

Steve Dezii (left) and Steve Wynn (right) in Mr. Wynn's office in Las Vegas, Nevada (2013). -

Advisory Board meeting in Las Vegas (2016). Back row, left to right: Mitch Beckman, Sara Volz, Cammy Seamans, Ed Stone, Donnita Gross, Gary Seamans, J Nelson, Marty Carver, Luan Streb. Front row, left to right: Steve Dezii, Melodey Dezii, Paul Rosenthal, Julia Furrow, Leo Hauser, Brian Walker (2017). -

Advisory Board meeting in Paul and Carla Rosenthal's home in Washington, D.C. (2018). Foreground, left to right: J Nelson, Brian Walker, Steve Dezii, Paul Rosenthal, Julia Furrow, Mary Stone, Leo Hauser. Background, left to right: Allie Rosenthal, Pete Matthes, Ira Rosenmertz.

A two page "Navigational Chart to the Cures" was created which among other things stated the principle of freely sharing everything we learned with other groups: our protocols, our blueprints, our regulatory documents - everything - so that others could copy what we were doing if they were so inclined. Shortly after presenting these ideas publicly for the first time someone asked Stone "what if someone steals it from you?" Stone replied, "Well, that would be like stealing my lawnmower and mowing my lawn."

While devising this local manufacturing strategy, IVR scientists developed their clinical gene therapy experience by continuing their collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania to treat RPE65-associated Leber congenital amaurosis with AAV-mediated gene therapy. In March of 2013, Steve Russell performed the first subretinal gene therapy at the University of Iowa and would later be the first author of a paper in the Lancet describing the successful phase III study of this treatment.

At about the same time, Stone's lab discovered a mutation in the MAK gene that is responsible for 35% of all retinitis pigmentosa in people of Jewish ethnicity. This discovery attracted the attention of the Nevada businessman Steve Wynn who in turn asked his friend and colleague of 40 years, Steve Dezii, to travel to Iowa and check out the new institute. Dezii spent three days in Iowa City talking with every scientist and opening every drawer and every closet and asking what the contents were for. He flew home to Las Vegas and told Mr. Wynn, "I have visited every lab in the world that works on inherited eye disease, and in my opinion, Iowa is your best chance of getting your vision back." Soon thereafter, Dezii and his friend Ira Rosenmertz both joined the IVR advisory board.

In 2013, Mr. Wynn made a 20 million dollar gift to the institute to, among many other things, build a GMP manufacturing facility for both gene and stem cell therapy. This facility is named for Steve Dezii in recognition of his many years of service to the international vision research community and his dedication to finding effective treatments for all people with degenerative retinal diseases.

Soon thereafter, Mr. Wynn introduced Stone to Los Angeles businessman Howard Ruby and his wife Yvette Mimiuex (the actress) who also traveled to Iowa City to meet the team and listen to their strategy for restoring vision to visually impaired people. Within days of his visit, Mr. Ruby made a gift of five million dollars to establish the Ruby Human Retinal Engineering Laboratory with an associated endowed chair. Some of these funds were also used to purchase a 3D printer capable of printing biopolymers with features as small as 75 nanometers. At the time, this was only the fourth instrument of its kind in the United States and the only one used for a medical purpose. Acquisition of this instrument was a major step toward restoration of vision because the biopolymer scaffolds printed with it increase the survival rate of transplanted retinal precursor cells as much as 40-fold.

-

Ed Stone and Sam Walker on the course at Sam's Scramble for Sight, Egypt Valley, Grand Rapids, Michigan (2019). -

In 2018, the "Heart of Our Mission Award" at Sam's Scramble for Sight was a Fender Telecaster guitar, signed by Bruce Springsteen, presented in absentia to the recipient Budd Tucker. Left to right: Brian Walker, Sam Walker, Steve Visser, Gary Seamans, Virginia Visser, Matt Sova (as Bruce Springsteen), Cammy Seamans, Daphne Carver, Mimi Carver, J Nelson, Steve Dezii, Ed Stone. -

Buddy Lazier (seated in his 2014 Iowa Vision Research Indy car) poses with many of the IVR faculty and staff before serving as the Grand Marshall of the 2014 University of Iowa homecoming parade in downtown Iowa City.

In 2012, Brian Walker was the CEO of the furniture company Herman Miller. His son Sam went in for a routine eye exam and was found to have retinitis pigmentosa. Shocked by this news, Brian called Steve Wynn for advice and was put in touch with Steve Dezii who in turn arranged a visit for the Walker family to Iowa City. A few months later, Brian joined the IVR advisory board and as one of his first contributions, planned a large golf tournament in Grand Rapids, Michigan (Sam's Scramble for Sight) that has since been held annually on the anniversary of Sam's diagnosis. This event has raised millions of dollars for vision research and directly resulted in the discovery of the gene TRNT1, one of the rarest causes of RP, as the cause of Sam's vision loss. One of Brian's friends, Brock Walker (no relation) is a former professional skier and chiropractor who is perhaps best known for designing the Formula 1 racecar seat that allowed Buddy Lazier to win the 1996 Indianapolis 500 only a few months after breaking his back in a crash. The remarkable coincidence that Buddy's daughter has an inherited eye disease brought Brian, Brock, Buddy and the IVR together at the 2014 Indy 500 with "Iowa Vision Research" prominently displayed on the side of Buddy's car. Elliott Sohn, an IVR faculty member and vitreoretinal surgeon met Buddy at Indy and later began racing open wheel formula cars himself with Buddy's encouragement. Elliott and Buddy's son Flynn have continued to use their racing to help spread awareness of inherited retinal disease in general and the IVR in particular. In 2019, Flynn Lazier won the Formula Atlantic championship with the IVR logo on his car.

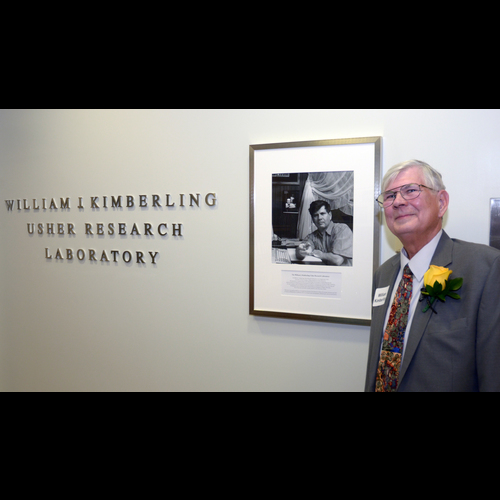

Dr. William Kimberling is a human geneticist in Omaha, Nebraska who dedicated his long career to studying genetic causes of deafness and combined deaf blindness. He and Stone collaborated for many years to study patients with Usher syndrome and when Bill retired in 2013, an arrangement was made between Boys Town National Research Hospital and the University of Iowa to transfer all of the samples and research data Bill collected to the IVR for further study. An Usher Research Laboratory in the IVR was named in Bill's honor and a ten million dollar philanthropic campaign was launched specifically to support Usher Research. Howard and Yvette Ruby, Scott Dorfman and Susie Trotochaud, Ira and Helen Rosenmertz, Brian and Colleen Walker and many others have generously supported this campaign which at the time of this writing is nearing its successful conclusion.

-

Bill Kimberling at the dedication of the Kimberling Usher Research Laboratory in the Institute for Vision Research (2017). -

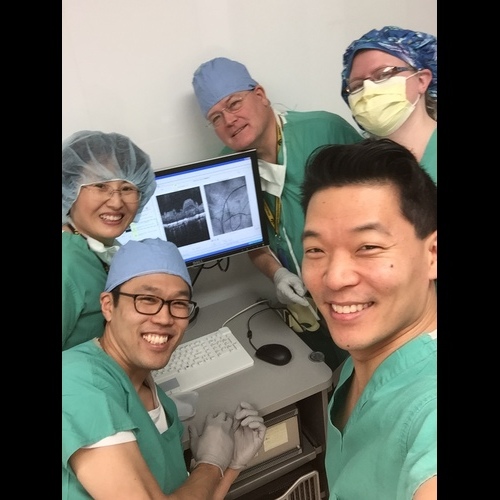

IVR experimental surgery team. Clockwise from lower left: Ian Han, Chunhua Jiao, Steve Russell, Emily Kaalberg and Elliott Sohn (2017) -

Installation of Robot 1 in the Ruby Human Retinal Engineering Laboratory (2017). -

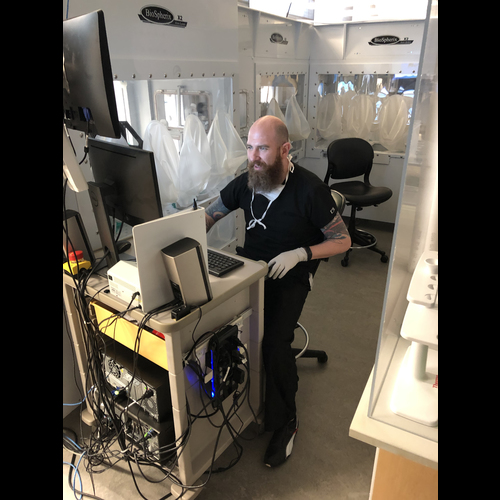

Budd Tucker at the command console of Robot 1 (2020). -

Yvette Mimieux Ruby's art studio in Beverly Hills, California. Left to right: Howard Ruby, Ed Stone, Mary Stone, Yvette Mimieux Ruby, (2018). -

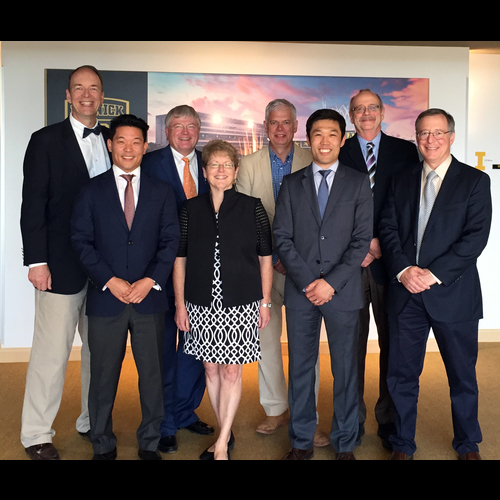

University of Iowa Retina Faculty, 2018. Left to right: Ed Stone, Elliott Sohn, Steve Russell, Karen Gehrs, Michael Abramoff, Ian Han, Jim Folk, Culver Boldt.

In 2016, Ian Han was successfully recruited to the IVR and vitreoretinal surgery service against stiff competition from Johns Hopkins and Duke; in 2017 our former postdoctoral fellow Luke Wiley joined the IVR faculty with an interest in the role the immune system plays in retinal degeneration; and in 2019, our former fellow Elaine Binkley returned to our vitreoretinal surgery service and the IVR faculty with a specific interest in intraocular tumors.

Also in 2019, John Butler and his wife Alice made a five million dollar gift to the IVR to accelerate the development of the robots that will be needed to increase the manufacturing throughput of stem-cell-based photoreceptor grafts from less than a dozen to several hundred per year.

From 2010 to the time of this writing (mid-2020) the IVR faculty published 186 papers together and five of these are currently being cited more than 20 times per year. The importance of these papers stems from the true interdisciplinary nature of the research team and the incomparable size and quality of the collections of DNA samples (over 75,000), human donor eyes (over 2700), patient derived cell lines (over 3000), research subjects with confirmed genotypes (over 6000), research fundus photographs (350,000 - oldest from 1962) and research Goldmann visual fields (50,000 - oldest from 1953). For example, the paper that Stone feels will end up as the most important of his career reported the clinical and genetic findings from 1000 consecutive families (more than 3000 individuals) seen over a period of five years in the inherited eye disease clinic of the University of Iowa.

-

Scott Whitmore (left) Adam DeLuca (center) and Jean Andorf (right) examine the pedigree of one of the larger families studied by the Molecular Ophthalmology Laboratory (2018). -

High-throughput 35 mm slide digitizing device. The greatest challenge of digitizing the tens of thousands of mounted 35mm slides in the departments photofile collection was mechanically handling slides of various ages and thicknesses without jamming. The Kodak carousel projector has the lowest jam rate of any slide handling device ever made. These projectors were fitted with a white-balanced LED light source and a 35 mm camera to digitize the entire inherited retinal disease collection of the department dating back to the early 1960s. -

Some IVR teammates pause for a photograph (2018). Left to right: Miles Flamme-Wiese, Emily Kaalberg, Cathryn Cranston, Erin Burnight, Katherine Gibson-Corley and Laura Bohrer. -

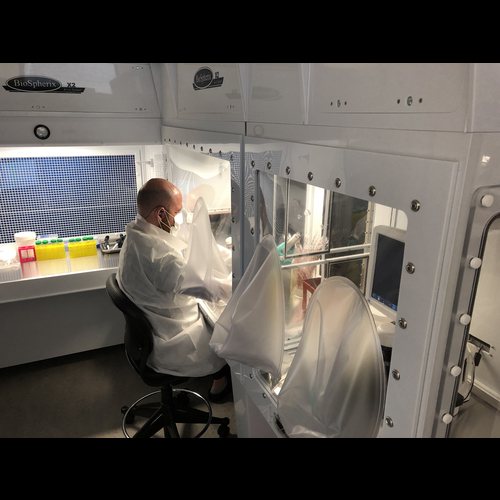

Budd Tucker works in a temperature, gas and humidity controlled Biospherix cabinet to feed human stem-cell-derived photoreceptor precursor cells without subjecting them to injurious environmental variations associated with conventional cell incubators (2018). -

The bioinformatics team celebrates the safe return of one of their very valued colleagues (2016). Top, left to right: Ed Stone, Todd Scheetz. Row 2, left to right: Wes Goar, Nick Lessing. Row 3, left to right: Laura Shepard, Ben Faga, Isaac Helgens, Adam DeLuca, Lexi Burnight, Nicole Tatro, Mark Christopher .

The incredibly short death to preservation times of the eyes in the IVR's research eye bank allowed Rob Mullins, Drew Voigt, Scott Whitmore, Adam DeLuca, Todd Scheetz, Miles Flamme-Wiese, Elaine Binkley and their colleagues to perform the first definitive single-cell RNA sequencing studies of the retina.

The extraordinary amount of philanthropic support of the IVR coupled with thousands of patient derived cell lines allowed Budd Tucker, Erin Burnight, Luke Wiley, Kristin Anfinson, Emily Kaalberg, Katie Cranston, Jess Cook and Laura Bohrer to model multiple inherited eye diseases in vitro and also to develop GMP compatible methods for creating transplantable polymer-supported grafts of retinal precursors. Elliott Sohn, Steve Russell and their colleagues refined the instrumentation and surgical technique for transplanting these grafts into a porcine model of retinitis pigmentosa while Ian Han and others developed new rat models of retinal degeneration and developed methods for transplanting miniature grafts into the subretinal space of their eyes.

In addition to these peer reviewed publications, Terry Braun, Todd Scheetz, Adam Deluca, Jean Andorf, Heather Daggett, Jeremy Hoffman, Ben Faga, Matt Jack, Nicole Tatro, Nick Lessing, Ed Stone and others devised a freely accessible web-based teaching system known as Stone Rounds (www.StoneRounds.org) that currently contains anonymized clinical images from hundreds of molecularly-confirmed patients with diseases distributed across the entire spectrum of inherited retina disease. The team's goal is to eventually add over six thousand patients to this site.

The Pandemic before the Cure (2020)

The "history of the IVR" will not be complete until retinal degenerative diseases are being slowed or stopped with affordable gene therapies and vision is being restored with stem cell transplantation. At the time of this writing, the world is in the throes of a dangerous pandemic and our country is racked by political upheaval. The economy is weak and likely to weaken further and a vaccine for the virus is at least 6 months away. Despite these challenges, the faculty and staff of the IVR remain optimistic and completely committed to their mission and each other. They have devised a 50% work at home strategy to maximize social distancing while still getting the lab work done and have designed their own PCR and antibody-based tests for the Covid 19 virus and are performing twice per week testing of the entire IVR work force. Stone has converted his weekly teaching sessions to a teleconference format that is attended by ophthalmologists and vision scientists from all across the country with a few attendees from Europe and the Middle East as well. The institute is less vulnerable to the vagaries of state and hospital finances than other units on campus because of their endowments, their robust relationships with their advisory board members and other generous philanthropists, their efficient development team (led by Katie Sturgell), their exceptionally high scientist to administrator ratio; their culture of mutual support; and, perhaps most importantly, their remarkable constancy of purpose. The group is working hard to protect all of its members and all of its irreplaceable collections through the remainder of the pandemic and is poised to begin clinical trials of their first IVR-manufactured therapies once a vaccine is available and the threat to their patients' and colleagues' eases.

-

Advisory Board dinner in the home of the University president's home in Iowa City (2015). Left to right: Interim UI President Jean Robillard, Leo Hauser, Julia Furrow, Cammy Seamans, Marty Carver, Reneé Robillard, Rob Mullins, Paul Rosenthal, Incoming UI President Bruce Harreld, Todd Scheetz, Mike Wagoner, Gary Seamans, Ed Stone, J Nelson, Mary Harreld, Brian Walker, Luan Streb, Budd Tucker, Pete Matthes, Retiring UI President Sally Mason, Mike Anderson, John Fingert, Ken Mason, Mitch Beckman. -

Close friends and colleagues Rob Mullins (left) Ed Stone (center), Budd Tucker (right), 2017. -

Mary and Ed Stone at the American Ophthalmological Society (2017).